Every level in our upcoming game is a handcrafted masterpiece. Except, well, it’s not crafted by a hand. It’s built by algorithms with questionable ethics and a flair for chaos.

So… How do you teach a game to make levels?

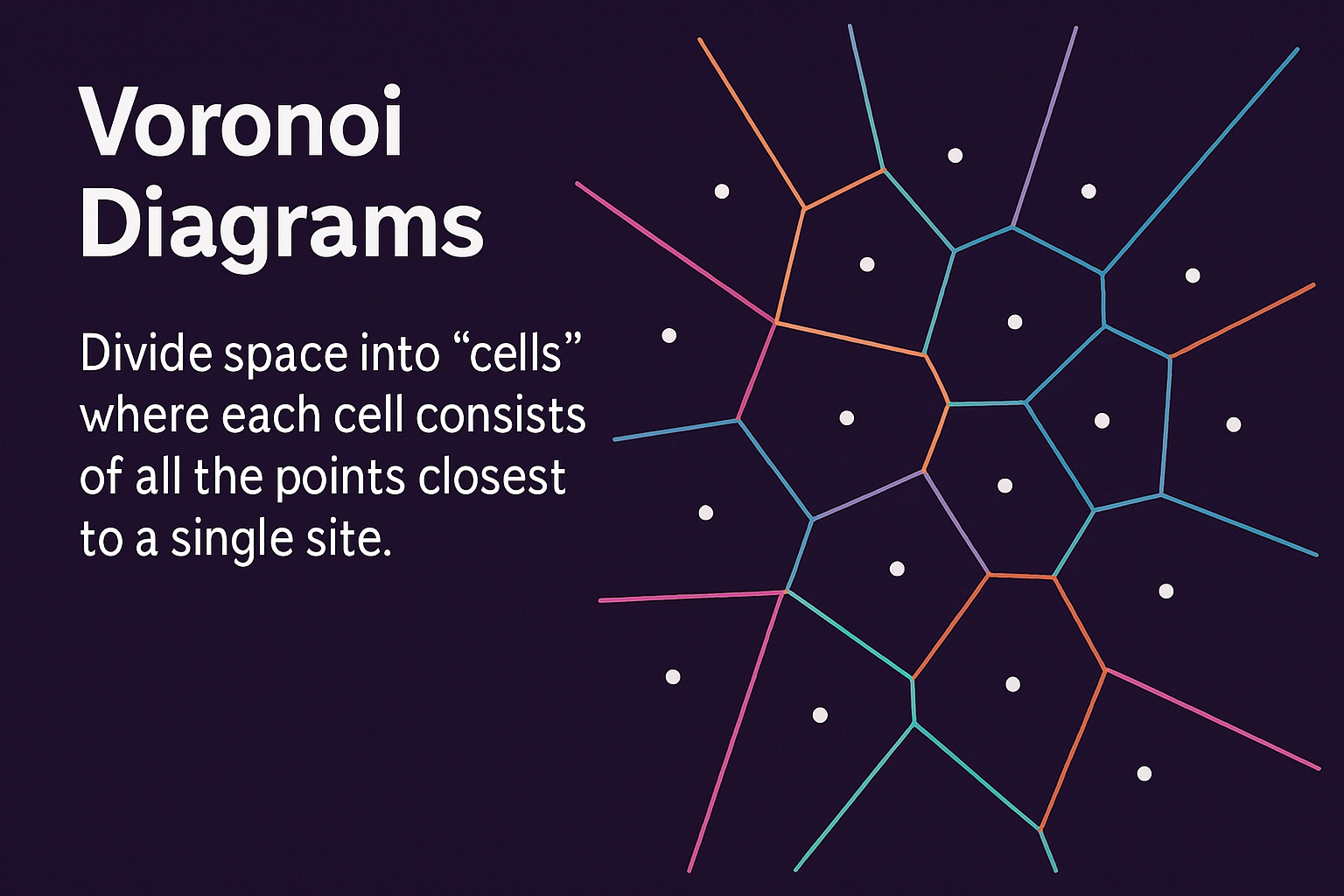

Glad you asked. We started with something elegant: Voronoi diagrams. These divide space based on a bunch of randomly scattered points (called “sites”). Like cells in a petri dish getting into turf wars, each site claims a chunk of space that it’s closest to. And if you’ve played Unexplored 2, you’ve seen how Voronoi-based worlds can feel weirdly… alive.

To keep things fast and efficient, we used Fortune’s algorithm, a sweep-line algorithm that builds the entire Voronoi graph in O(n log n) time. In simple terms? It’s fast. Like, scary fast. And it gives us a map full of lovely, organic-looking cells that are just begging to become rooms.

Voronoi Cells Aren’t Rooms… Yet

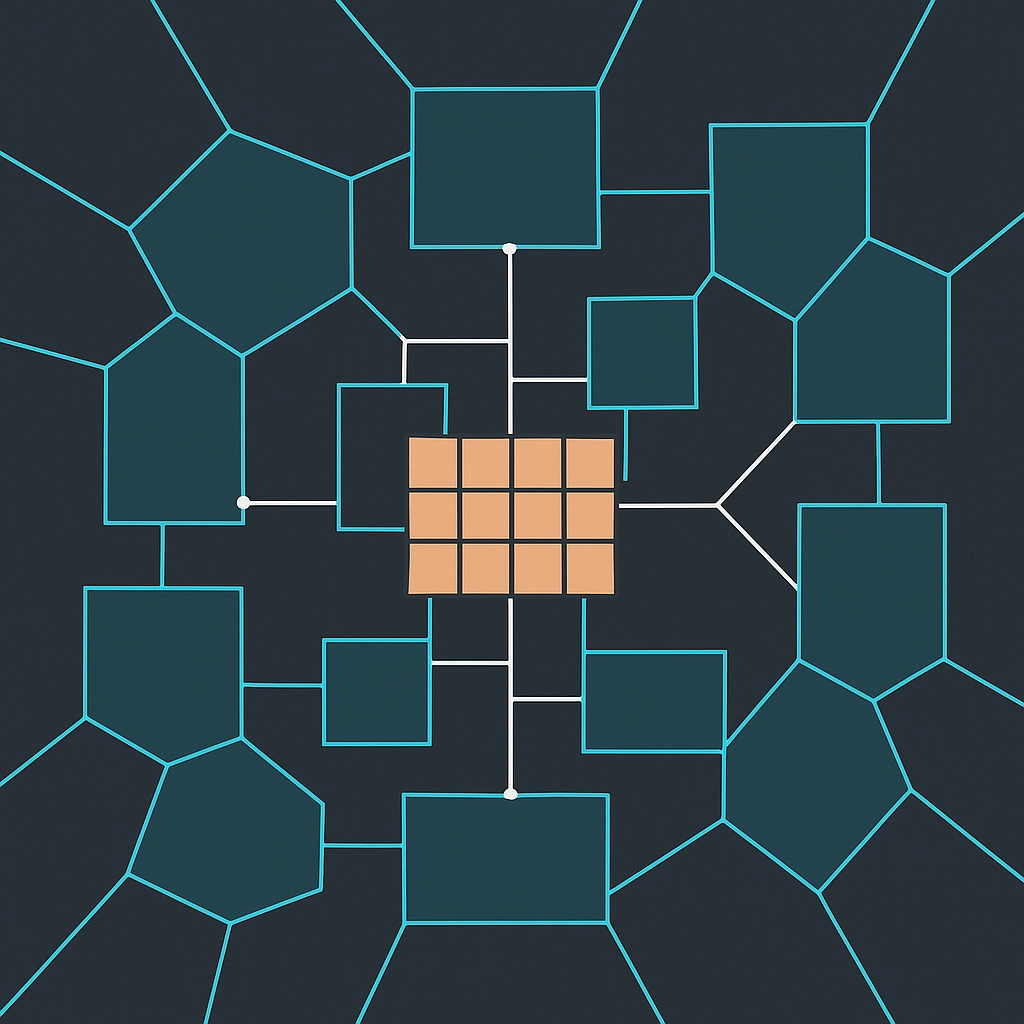

Here’s the problem: Voronoi cells are often janky polygons with weird angles. And nobody wants to fight demons in a room shaped like a potato chip. So we straighten them out.

We take each edge of every cell and pivot it around its center to form rectilinear shapes. Basically rooms that follow a grid and don’t make the player’s eyes bleed. If gaps appear, we fill them with new edges that match the layout. Think of it like trimming a bonsai tree, if the tree was made of geometry and passive-aggressive decisions.

Taming the Overlap Gremlins

Sometimes, the resulting rooms overlap or produce slivers that look like error messages in physical form. So we gave the first room dibs. The first room placed gets to lock in its edges. Everyone else has to play nice—or get deleted. This rule drastically cuts down on weird, overlapping rooms and reduces the chance of spontaneous rage-quitting.

Doorways, DFS, and Dungeon Flow

Once the rooms are finalized, we build the backbone of gameplay: connectivity.

We use Depth-First Search (DFS) to crawl through the rooms, connecting them with doorways in a way that ensures every room is accessible. It’s not just random door spam, we’re crafting a path. And during that crawl, we tag the starting room (where the player spawns) and the last room encountered during the search (which becomes the exit or boss arena). It’s controlled exploration with graph theory wearing a flamethrower backpack.

The result? Levels that are:

- Fully explorable

- Naturally progressing in difficulty

- Varied enough to stay fresh, run after run

But why build it this way?

Because it works. Games like Spelunky, Enter the Gungeon, and others use procedural generation to great effect.

But those games are have had their turn. I’m building on the bones of their ideas, adding layered mechanics, narrative breadcrumbs, and multiple interconnected systems. It’s not just about replayability; it’s about player-driven discovery.

And why This Matters

Most procedural systems aim for variety, ours aims for structure with surprise. You’ll never run the same layout twice, but it’ll always feel like it makes sense. Like someone built it to just for you.

This process isn’t final. We’re still tuning the algorithm, adjusting edge rules, and debating whether lava should be a feature or a bug. But what we’ve got already feels good: a balance of order and chaos, geometry and gameplay.

And if you ever find yourself sprinting down a hallway wondering who built this architectural horror show… now you know. It was me. You’re welcome.

Stay tuned. There’s more madness to come.

– Guts Glory Games